By Phil Ehrensaft

The long Appalachian ridge that stretches from North Mountain in Virginia through the town of Rosendale in New York State is destined to be one of America's principal environmental battlegrounds. This unique and knock-down gorgeous habitat is within easy driving distances from three of the nation's principal megalopolises: metro D.C.-Baltimore, greater Philadelphia, and the Big Apple, which now sprawls across four states. Sharply contrasting ambitions and visions concerning the human uses of the ridge create, and will continue to create, a flow of conflicts along its entire southwestern to northeastern axis.

Two kinds of conflicts are involved. First, there are the big, public battles over big projects like the one over the proposal to turn the fragile lands of the 2,500 acre Awosting Reserve in Gardiner, NY, into a gated luxury housing estate and international golf course. Three years of heated debates within the town, and the forging of alliances between community activists and national environmental organizations, have resulted ultimately in the land becoming part of the Minnewaska State Park Preserve.

Second, there are the smaller "death from a thousand cuts" individual projects which may, in the aggregate, have an even greater environmental impact than the biggies. These involve hundreds of decisions by local planning boards and zoning boards of appeal. To my knowledge, no one is keeping a systematic account of these myriad local decisions.

From an environmentalist's point of view, not all of these conflicts, big or small, will have such a happy ending. You win some, you lose some, or you get to some kind of draw. Whatever the outcome, these environmental conflicts impose heavy demands on the time and energy of the local citizenry. Given that my kitchen window lies about 25 yards from a long boundary with the erstwhile Awosting Reserve, I speak from very personal experience. On the other hand, participating in debates within the community can increase citizens' sense of place and involvement in community affairs. That's what happened in Gardiner, and it turned out to be worth a lot.

| |

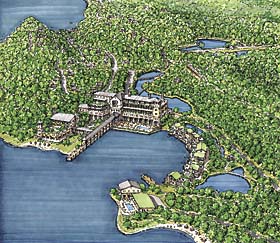

Aerial view of proposed Williams Lake development in the town of Rosendale.

|

There are big-time project proposals all along the New York State portion of the Appalachian ridge we call the Shawangunk Ridge, the word "Shawangunk" perhaps being the result of an early Dutch colonial transliteration of an Amerindian appellation. The fact of the matter is that if we don't look at these projects with an eye towards

responsible and

sustainable development, we'll be in for a whole heap of trouble.

Here are the current projects being proposed for development on the Shawangunk Ridge worth paying attention to in terms of their environmental impacts: a 1,145 acre gated housing development along Williams Lake in Ulster County's town of Rosendale, a project which would also restrict citizens' traditional access to the lake. In the town of Deerpark, Orange County Holding Company wants to build 354 single-family units, two retail developments, and recreational facilities on an undeveloped site of 636 acres adjacent to the Bashakill Wildlife Management

Area.

The small town of Mamakating in Sullivan County has not one but four pending projects: first, the 750 acre Seven Peaks project which would sprawl along both sides of the ridge. Then there's the proposed 450 acre, densely populated planned Hasidic community of Kiryas Skver. In environmental terms, high density could potentially result in sounder development than is the case for most sprawling suburbs and exurbs — if there's serious planning in that direction, that is.

Third, there's the now-regionally-famous proposal forwarded by the Japanese company Yukiguni Maitake for a major mushroom-growing and processing facility in the Basha Kill area. If not handled properly, this kind of facility can wreak havoc on local water systems. Fourth, there's the Kingwood Subdivision proposal that would appear to introduce classic suburban sprawl across Mamakating and Thompson, with an industrial park to boot.

In Cragsmoor, there are questions of how a proposed large Buddhist retreat will impact this small village on a wide range of issues from water-use to clogged roads and traffic noise. Then there's the never-ending Sullivan County quest for casinos, with the same range of questions about impacts on a much larger scale. It's not as if Sullivan County couldn't use an industrial park in order to help revitalize its economy — the question of concern to the environmentalist is whether this one would use readily available green building technology and planning.

A few weeks ago, I would have also listed the New York Regional Interconnect (NYRI) power transmission line, which would have savaged a wide swath of small and rural New York State, the Shawangunk Ridge included, in order to construct power lines to further supply New York City with electricity. The political powers that be responded to widespread and strongly voiced opposition to NYRI's attempts to gain extensive powers of eminent domain, plus seeking permission to pass on the cost of this mega-project to consumers. That project is no more, much to the environmentalist's relief.

Above and beyond the specifics of either big projects or smaller slice-and-dice efforts, the future human uses of the Shawangunk Ridge, and the cousin sections in Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, touches the fundamental paradoxes of sustainable economic practices.

In terms of water resources, the ridge is central to the hydrological flows that feed the water systems of adjacent communities. Building too many houses or commercial facilities that intercept too much of the ridge's water supply will disrupt the hydrology over a wide region. Build too many impermeable surfaces for too many roads, parking lots, and current roofing practices, and too much water will shoot too quickly down the slope. The ridge is also an invaluable source of biodiversity, including unique plant and animal species meshing in complex communities which we are just beginning to understand. When that's disrupted, Mother Nature presents a stiff bill.

In short, development by its very nature has an indelible impact on the environment, whether it's billed as "green" and "sustainable" or not.

Despite this fact, many of the suburbanites who are now the dominant American demographic group, not to mention people in central cities, cherish open space like the ridge. If too many people from metro New York, Washington, and Philadelphia actively exercise that desire, green space will be seriously disrupted. Just how do we plan around that?

Which brings me to the factor with perhaps the biggest impact: high-tech, and high-level, professional services that have migrated to the outer suburbs. This dispersion of jobs makes it practical for people to live in small towns on the ridge, which turn into "exurbia." But because of the impacts that development on the ridge can cause just in terms of disrupting the environment's delicate homeostasis, what's practical for us winds up being potentially disastrous for the green, open spaces that we've grown to treasure. We're now coming to understand the effects that our long-time, small community settlements have had on the ridge — it's important to make sure that we keep those impacts in mind while newcomers plan their developments.

Indeed, this type of piecemeal, exurb development ultimately can hit the environment harder than ten mushroom plants. Unless we strive to adopt wise settlement patterns, and introduce green building practices that make a whole lot more sense than what we're doing now and what we've been doing for generations, we could end up losing it all in the long run. It's one thing to admire the area for its beauty and bucolic splendor…but when that admiration leads to eager and irresponsible over-development, the lush, green ridge that brought us here in the first place will be nothing but a long-gone memory.

[ Rate Card ] [ Advertisers ] [ Contributors ] [ info@gunkguide.com ] [ home ]