By Marc B. Fried

B

ack in the 1950s and '60s, if you mentioned the Shawangunk Mountains to someone only vaguely familiar with the ridge, you sometimes got the response, "Oh, you mean the foothills of the Catskills?" Nothing made me madder. Ellenville historian Katharine Terwilliger felt the same way, and even had a sign made, at her own expense, informing people on Route 52 at the east edge of the village that "You are in the Shawangunk Mountains." When Ice Caves Mountain Inc. opened for business at Sam's Point in 1967, they advertised their attraction as being in the Catskills. I took issue with this display of ignorance in a discussion with one of the owners, and he replied, "When Grossinger's and the Concord start saying they're in the Shawangunks, we'll do the same."

Grossinger's and the Concord are long since gone as Catskill resort hotels, and "Ice Caves Mountain" is but a memory. Meanwhile, the Shawangunks years ago came into their own, not as a "speed bump en route from the Hudson to the Catskills" — another unfortunate characterization — but as a world-class natural wonder in their own right. I knew it all along.

Geologically, botanically and scenically, two mountain ranges could scarcely be more dissimilar. The Catskills, in a strict geological sense, are not even a true mountain range at all (OK, I'm getting even): they were formed when a high, level-bedded plateau was slowly eroded by streams. The remnants of that plateau, between the many stream valleys and ravines, are the Catskill peaks we see today. The much older Shawangunks, on the other hand, lie in a true orogenic zone, created by an abrupt upward folding of the earth's crust, much as you might produce a longitudinal ripple in a sheet of paper by pressing sideways from the two side edges of the sheet.

There are folded mountain ridges all through the Appalachians, but what makes the Ulster County Shawangunks unique is the white quartzite conglomerate that caps this part of the ridge and protects the soft, underlying shales from erosion. This cap-rock is harder than granite and forms the ridge-top escarpment, the vertical cliffs for which the northern Shawangunks are famous. Because it's extremely resistant to weathering, the soil formed from this rock is very thin and poor in nutrients. It is also very acidic. These factors help give us the vast dwarf pitch pine barrens and the acid-loving huckleberries, cranberries, rhododendron, mountain laurel, and other members of the heath family that clothe the ridge. They form a fire-dependent ecosystem, whose flora thrive not only from the soil character but from the frequent wild fire that has swept across the Shawangunk ridge for millennia.

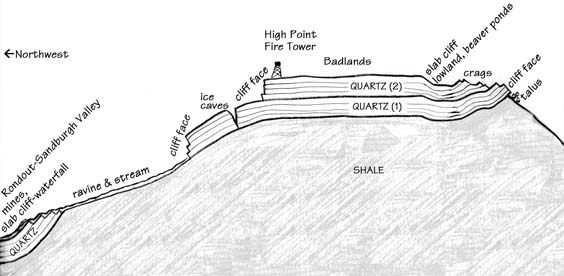

The cliffs of the Shawangunks are most dramatic at the exposed edge of the quartz layer, overlooking the Wallkill Valley, but are found elsewhere wherever various geological forces have resulted in differential erosion. At the risk of oversimplification, the mountain may be understood in terms of two quartz layers, separated by a thin deposition of a softer, less cohesive sediment. Thus, for example, in Minnewaska State Park Preserve, we have the Castle Point / Kempton Ledge escarpment (the top layer) and the Hamilton Point escarpment (below), the two running parallel and separated by a shoulder about a quarter-mile wide. Both make an acute angle at the head of the Palmagat and head south, but only the lower layer makes it all the way to Gertrude's Nose, where it takes another sharp turn, northeastward toward Millbrook Mountain, the Trapps, and Mohonk. The upper layer is confined to the northeast side of the powerline that crosses the Gertrude's Nose ridge. The vertical cliffs from Millbrook Mountain northeast to Mohonk are the highest of the Shawangunks because the exposed edges of the two quartz layers are stacked one directly atop the other.

Another place where the two layers are differentially eroded is in the Verkeerder Kill area, where the edge of the bottom layer forms the cliff over which eighty-foot Verkeerder Kill Falls tumbles, while the edge of the upper layer runs northwest to High Point, forming an escarpment perpendicular to the ridge, overlooking the upper basin of the Verkeerder Kill and forming the west wall of the Badlands plateau. From High Point, this escarpment marking the edge of the top layer of quartz may be traced eastward and then northward, well beyond Napanoch Point, then southeastward past Decker's Pond to Stony Kill Falls, and finally northeastward, to where it dissipates approaching Route 44/55 near the Sanders Kill.

Faults occur in places, making for a more complex physiographic picture: part of the northwest shore of Lake Awosting is composed of a fault, with bedding strata turned 90º from horizontal, and the long cliff paralleling the northwest side of the lower Fly Brook and the Peters Kill, from near Lake Awosting northeastward, is undoubtedly caused by a "dip-slip" fault. This cliff face (the fault's "hanging wall") is actually composed of the same upper layer of rock that continues on the southeast side of the kill (the "foot-wall") up toward the Kempton Ledge escarpment. But southeast of the hanging wall, the layer is sunken ("down-dropped") along a northeast / southwest axis (the fault's "trend" or "strike"), forming a depression along which the stream flows. A mile to the northwest, Stony Kill Falls tumbles ninety feet over this same upper layer of quartz, and below the falls the Stony Kill runs along the top of the lower quartz layer.

The geology of the Shawangunks down to the Rondout Valley.

Illustration by Marc Fried |

Among the most beautiful and geologically interesting of the watercourses in the Shawangunk Mountains cascades down through the Witches' Hole, the huge ravine on the mountainside above Napanoch. The main branch of the stream begins as Beaver Brook, in level wetlands just below the High Point escarpment. The brook flows across the top of the bottom quartz layer, picking up speed as the incline steepens on the convex mountainside. The water then flows down off the edge of this lower quartz layer into a large "window" of underlying shale bedrock. The potential existed for a major waterfall here, but instead the stream cascades over a series of small ledges, with much of the water descending hidden in cracks and crevices. A huge, three-branched ravine opens up in the underlying shale, and, not to disappoint, the brook's main branch soon drops over black shale in a nameless, fifty-foot fall that is the most remote and inaccessible of the Shawangunks' nine major waterfalls.

Intermittent quartz cliffs rim the perimeter of this shale-bottomed ravine, and are visible from the Rondout Valley, especially when illuminated by mid-day sunlight. Nearing the bottom of the mountain, the quartz layer begins to close in on the ravine, finally coming back together and closing up this window of exposed shale. When the brook encounters this "cliff" of quartz, it must climb "uphill," geologically speaking, to the top of the quartz layer. Since it does so in a series of small steps, and since the quartz conglomerate beds are pitched steeply downward toward the valley, the stream does not of course actually have to flow uphill for any significant distance. It forms small pools as it meets each successive stratum of the overlying rock, then rushes down the steep incline of the bedding plane until encountering the next stratum. Finally, it carves a very narrow (though not deep) gorge as it fights its way through the last beds of impossibly hard quartz rock, the only place on the mountain where such a gorge occurs. A similar dynamic occurs near the bottom of North Gully ("Mountain Brook"), just outside of Ellenville, giving rise here, not to a narrow quartz gorge, but to some beautiful "potholes" in the stream bed.

There is much to see in the Shawangunk Mountains from the marked, maintained hiking trails and carriage roads, but there is more to see by also rock-hopping up or down its streams and following its cliff lines wherever they may lead. This, of course, may occasionally bring you into conflict with legal eagles or private landowners, who, however, are likely to be somewhat more understanding if you seem to know what you're doing: this includes familiarizing oneself with, and carrying, USGS topographical maps, and being equipped with a compass, first aid (including, most importantly, a wide Ace Bandage), snake-proof gaiters and snake-bite kit if necessary, and food, water, clothing, and footwear appropriate for whatever weather the mountains might possibly throw at you. A cell phone is excellent in case of serious injury, but is no substitute for proper gear and intelligent planning.

But even if you come to know the Shawangunks primarily by looking up from its neighboring valleys, the experience can only be enhanced by understanding something of the geological forces and influences that have shaped these mountains into such an imposing piece of terrestrial architecture.

[ Rate Card ] [ Advertisers ] [ Contributors ] [ info@gunkguide.com ] [ home ]